![]()

Imre Nagy’s first term as prime minister: reform instead of corrective measures

|

| J.V. Stalin in about 1950 |

After Stalin’s death 1953, the leadership in Moscow began to plan changes in Soviet foreign policy. The bad relations with Yugoslavia were to be mended and the country enticed back into the communist camp. A solution was to be found to the German and Austrian question, which had been dragging on since the Second World War. These considerations lent importance to Hungary, which bordered on Yugoslavia and Austria and had played a prominent part in branding as a renegade the communist Tito regime in Yugoslavia. Furthermore, it had shared several hundred years of history with Austria, as part of the Habsburg Empire before 1918.

In June 1953, a group of leading communist politicians was summoned to Moscow. There the Soviet leaders, headed by Beria, unsparingly criticized the policy of the Hungarian Workers’ Party (HWP), which rapidly produced an explosive situation back home. The recommendations made by the leaders of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) were designed to provide background support for a partial change in the Soviet political line and avert an imminent economic collapse in Hungary. They were coupled with personnel changes, notably the appointment of Imre Nagy as prime minister. The Soviet intention was not to reform Hungary’s socialist system, but to forestall and manage an incipient crisis and prevent incidents that might interfere with the cautious opening that was planned in Soviet foreign policy.

There was certainly some economic justification for the Soviet political intervention. In its few years of rule since 1948, the HWP had brought Hungary to the brink of economic collapse. Reports reaching Moscow from various sources spoke of heightening tensions and a menacing level of discontent. The real income of wage-earners in 1953 had already fallen by 20 per cent since 1949.

The Hungarian leaders, on their return from Moscow, first announced the Soviet decision to the HWP Political Committee, which agreed to it, of course, and decided to convene a meeting of the Central Committee. Taking its cue from the Soviet criticisms, the Central Committee passed a tough, detailed resolution that named those really responsible for the crisis (or rather, the Hungarians among them). It condemned the party’s policy hitherto, including the forced industrialization (especially the unrealistic rate of expansion of heavy industry) and the neglect, exploitation and forcible collectivization of agriculture, which together had caused the steep decline in the living standard. These mistakes had been compounded by a campaign against society itself, with the spread of arbitrary, administrative methods and mass, unbridled terror. The whole country had been left at the mercy of a handful of men. The withering of party and social organizations had meant that these men could restrict even the communist party, the HWP, and its leading bodies to a semblance of political power.

Mátyás Rákosi, hitherto the country’s undisputed leader, responded in Moscow and in Hungary by going through the Bolshevik ritual of practising self-criticism—confessing his mistakes, or some of them. Far from conceding defeat, however, he did his utmost from the first moment to restore his authority (and his policies). Although he was unable to alter the Central Committee resolution—which would have amounted to open opposition to Moscow—he managed to stop it being published in the newspapers. Instead, the text informing the party was to be edited by the Political Committee. So the party resolution that criticized and condemned his policy and himself personally did not become public. It also meant that the general public heard of the new line of policy not from the party, as was customary, but from the new prime minister, Imre Nagy. This implied that the traditional bodies of government were gaining strength and independence by comparison with the party, or at least some freedom from its tutelage.

On July 4, 1953, the new Parliament elected in May convened.

|

| Rákosi

addresses a mass election meeting on May 10, 1953, in Kossuth tér, the square outside

Parliament in Budapest (MTI Photo) |

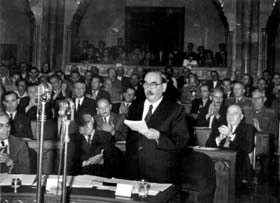

That was when Imre Nagy presented his policy statement as prime minister, announcing the new, more ‘people-friendly’ course. So there was a new prime minister, who no longer doubled as leader of the party, and his speech was a new departure, in content and in its tone and style, which was a marked improvement on the monotonous, declamatory addresses normally heard from functionaries of the party-state.

|

| Prime Minister Imre Nagy presents the government programme in Parliament on July 4, 1953 |

Imre Nagy was obliged to take over the leadership of the country in a situation that threatened to turn into a catastrophe. All he could trust, apart from his own convictions, was in the judgement and goodwill of the Kremlin, over which he had little influence, and in the genuineness of its moves to open up to the outside world. Imre Nagy had not been preparing himself to take over the leadership. His insight into the situation and his knowledge of it must have been limited. Though he had been a member of the HWP Secretariat and a deputy prime minister, the information would have filtered down to him indirectly, through the ‘foursome’ exercising real power. That flow of information had been augmented by what he heard in Moscow and the conclusions he drew from it. However, it all added up to too little for him to gauge the real situation and devise a comprehensive, systematic programme on which to base the work of his new government. So the directions from Moscow were the basis on which Imre Nagy had to take the measures required to avert the crisis. Only after stabilizing the situation to some extent might he have had a chance to work on a comprehensive political programme of his own.

Nor could Imre Nagy have remained long under the impression that the party leadership and apparatus shared all his enthusiasm for the reforms promoted by Moscow. At most he could hope that the apparatus of power, with hardly any change in its staff or mentality, would be disciplined enough to try to implement the central decisions. He could not expect the apparatus, in its confusion over the changes, to act as he would, or aspire or manage to correct at its own level the problems and conflicts that would inevitably accompany the New Course. Nor could he count on active support from the general public. Every organization in society, and the whole press and radio, which were capable of making the public’s voice heard or stifling it, remained firmly under the control and supervision of the communist party, which was still led by Rákosi.

Apart from these unfavourable circumstances for the new policy course, it began to suffer serious attacks, almost from the outset. Even while the Central Committee was still in session, Imre Nagy and Rákosi received a telephoned warning from Vyacheslav Molotov, a member of the CPSU Presidium. They were told that the draft resolution (which Rákosi had forwarded to Moscow as a final caution) contained exaggerations in its criticism of the period before 1953 and the consequent programme—and these were grounds for not publishing it. A few days after Prime Minister Imre Nagy had unveiled his programme in Parliament, the Hungarian leaders were summoned to Moscow again, to be briefed on a Soviet party resolution condemning Beria as a traitor. There Khrushchev emphasized that Beria’s ‘stance, how he behaved at the discussion of the Hungarian question, contributed much to his exposure.’

As he had with Molotov’s intervention on June 28, Rákosi immediately tried to harness this event in Moscow to his own campaign to regain power. Speaking at a meeting of party activists in Greater Budapest, called to instruct them in how to implement the New Course, Rákosi openly declared his opposing views, which gave the party apparatus and the state and economic organizations a legitimate excuse for resisting it.

The New Course concentrated on five areas of policy. The first and foremost objective was to rearrange the priorities in managing the economy. The absolute priority for industry and industrial development, especially heavy industry, ended. Industrial investment was reined in and the rate of industrial expansion slowed. This released funds that could be redirected to consumer-goods production, housing construction and agricultural development.

Redistributing the accumulation fund and radically changing the priority given to industry (especially heavy industry) caused numerous problems in several fields. For one thing, it undermined the policy-makers so far, by revoking what they had done and doubting and even disputing its effectiveness and propriety. The man compromised most by the package was Ernő Gerő, hitherto in charge of running the economy, although Imre Nagy badly needed his support and political alliance in the struggle against Rákosi. Gerő even showed some willingness to cooperate with Imre Nagy early in 1954—hoping to be the joyful third party who gained by their rivalry, obtained supreme power for himself, and concentrated it into a single individual’s hands again. However, Imre Nagy’s plans, especially his attempt to postpone the opening of the Stalin Ironworks, made Gerő more cautious, and Imre Nagy could no longer rely on him to any great extent.

The economic measures alienated not only Gerő, but all functionaries, at local or national level, who had been involved in the forced development of heavy industry or identified with it: factory managers, party branch secretaries, production managers, local-government officials, and powerful members of the central apparatus. For the system had rewarded its servants at every level, with extra pay, better housing, privileged access to goods, social rank, and the ear of local or national powers, through whom they could press their several, even personal interests. Any loss to this position (or feoff) of theirs reduced their status in the hierarchy. That gave them a material interest in obstructing or slowing the measures of the New Course that affected them directly, as they fully realized. Imre Nagy’s conflict with the managers of the economy, the National Planning Office, made him try to reform the way decision-making was prepared. This foundered on passive resistance there and in the HWP Planning and Financial Department.

Gerő and the segment of society just described effectively cited the problems that the changes were raising. It would cost the economy as much, they argued, to maintain the fabric of the suspended investment projects as to continue and complete them, even if the likely earnings from production were disregarded. They pointed to the spectre of unemployment, which would affect above all the workers in large-scale industry who formed socialism’s main base of support in society, so jeopardizing the building of socialism. They also brought up many other difficulties arising from the change in the economic structure. These were being compounded by the immediacy of the need for measures to avoid a crash, which left Imre Nagy no time to prepare a coherent programme in advance.

Lastly, but at least as importantly, the curb on the development of ‘socialist’ heavy industry detracted from the very legitimacy of the regime. The astronomical growth in heavy industry had been the ground chosen by the communists for proving that the socialist system of planning directives was superior to capitalist private enterprise. Furthermore, the relatively ‘conscious’ and well-organized work force in heavy industry was thought and proclaimed to be the system’s main basis of support. Steelworkers, miners, foundrymen and others had accordingly been given a privileged position. Developing heavy industry had been increasing the numbers and influence of a group in society that was thought to be strongly committed to the regime, so that the New Course was slowing down the building of socialism on that political plane as well.

So it was inevitable that Imre Nagy had to struggle repeatedly with forces eager to continue the forced development of industry. In the autumn of 1953, the National Planning Office implicitly took the position, in a contribution to the debate on the economic plan for 1954, that the measures of 1953 were meant to be just a temporary corrective for the economy. It would therefore be possible, the Office argued, to return to the original plan and economic model in 1954, in other words to a forced pace of industrialization. Imre Nagy had to debate long and hard before he could persuade the Central Committee on October 31, 1953 to alter its report, take his criteria into consideration, and declare that 1953 had brought a change in the Hungarian economy that was strategic, not limited to a six-month period. It was decided in the end that the task for industry in 1954 would be to consolidate the achievements so far. Priority would go to stimulating agriculture and food production.

The other important economic aspect of the New Course concerned measures to stimulate agriculture. With industry, the new policy still operated in the old way—through central decision-making in the form of central directives. In agriculture, Imre Nagy began to work to some extent by applying economic regulators and taking a rational, conventional economic approach. The forcible collectivization of land ceased and peasants were even given the option of withdrawing from the agricultural cooperatives they had joined. It became possible for individuals to rent uncultivated land on favourable terms. The compulsory deliveries of produce that the peasants were required to make were brought down and set for longer periods. A long-term development programme for agriculture was devised by involving Imre Nagy’s university colleagues and students and the best agricultural experts in the country. These measures served to resolve the immediate, acute crisis, improve supplies to the general public, and provide a basis for long-term development of the sector, along lines that accorded with the country’s specific characteristics.

Nonetheless, this group of measures was resisted as strongly as the shift of emphasis in industry. On the day after the prime minister’s July 4 speech to Parliament, the information system began to churn out warnings of village ‘rebellion’. Bonfires had been lit, it was reported. Imre Nagy had been feted till dawn, and according to the informants, whole villages had got drunk in some cases. The central authorities raised alarms about upsetting the money-goods relation and about urban famine ensuing from the reinforcement of peasant farming. It was constantly being claimed that the New Course was detrimental to the workers in heavy industry (by cutting jobs, or at least preventing new jobs from being created). Since the immediate beneficiaries were the peasantry, the property-owning peasantry, the measures threatened to overturn the worker-peasant alliance and distort the ostensible social foundations of socialism. Another objection was that agricultural policy could not be divorced from the economy as a whole. If private farming gained predominance, central control of the whole economy would be shaken. Furthermore, reducing the pressure on the villages would stem the flow of money available for investment in heavy industry.

The third important group of measures set out to raise the living standard of the population. One marked feature of the previous period had been a level of appropriation that exceeded what the general public could bear. This had been one of the main sources of finance for the forced economic growth. The investments and the costs of the bloated state bureaucracy, the armed forces and the police and security forces had been funded by extortion from the whole of society (to varying degrees). By bringing down prices, raising wages and setting lower performance norms, Imre Nagy was not opening the way for extravagance and luxury spending. He was simply easing a period of ‘seven lean years’ that had already lasted over a decade, if the wartime period is included. It was not a case of ‘eating the goose that lays the golden eggs’, as Rákosi claimed. Nor was the Soviet politician Lazar Kaganovich justified in telling a Hungarian delegation in May 1954, ‘You are living in greater style than your means permit. You are building socialism on credit.’ Imre Nagy had simply recognized that no one could expect a strong performance from a famished country or base a socialist society on a harassed, impoverished population. Imre Nagy realized that if the working class knew its basic needs were ensured, its will to produce and consequently its performance would increase. This in the longer term would provide the greater accumulation required for a somewhat higher level of personal consumption.

However, the efficacy of the price reductions was reduced by the steady fall in the quality of goods. Furthermore, the new measures had relatively sluggish effects on supply, which still left much to be desired, although the number of items in short supply decreased. There was a marked rise in personal consumption in 1954, to about 20 per cent higher than in 1950, but this still fell far short of what the intervening growth in national income might have allowed. The case was similar with the housing-construction campaign, which only eased some of the most pressing problems.

The most important, and certainly most spectacular measures of the New Course concerned restraining the excessive coercion of the authorities and relieving the oppression that weighed on society. The declared efforts to benefit the public would gain credibility only if it proved possible to curb the terror that played a key political and economic role in the operation of the system.

The amnesty measures that were taken fall into four main groups. First, large numbers of people were released from confinement, excused from paying fines, or relieved of various legal disabilities consequent on having a criminal record. Secondly, the government abolished several types of sentence and penal institution used in recent years. The internment camps were closed and sentences such as internal exile and designation of a compulsory place of residence were dropped. As the releases continued, the question of legal and moral rehabilitation began to arise. This would have meant naming those responsible for the miscarriages of justice, for if the mainly communist politicians leaving the prisons and internment camps were innocent, those who had sent them there must have been guilty. In the event the rehabilitation hearings were slow to begin. There were moves to shift the whole responsibility for the illegalities on Gábor Péter, the former head of the ÁVH (State Security Office), who had been arrested. On the other hand, it became increasingly recognized that Péter, whose personal responsibility no one could deny, had not run the ÁVH alone, without instructions from the party leadership, and that his writ had certainly not extended to the courts of law or the whole apparatus of power. Many people remembered the pronouncements by Rákosi, who had ascribed solely to his own vigilance the exposure of activity against the people by the ‘ Rajk gang’. It was clear that the real culprits were the top leaders of the HWP (and beyond them, the policies of the Soviet Union).

Society’s desire for justice coincided with Imre Nagy’s political instincts. The prime minister felt in any case, as a person, a need to name the chief culprit, and he recognized as a politician, early in 1954, that the greatest obstacle to implementing his June policies was the party chief, First Secretary Rákosi, who was also the one mainly responsible for the illegal acts. Rákosi would have to be removed from power before the policy of the New Course could develop. If accomplished, his removal would be in itself one of the great achievements of the New Course (if not its greatest single achievement). So the efforts to eliminate the illegalities, commence the rehabilitations and carry them out consistently came to the fore in Imre Nagy’s policy in 1954. This, apart from remedying deep grievances in society and proclaiming justice, would have removed Imre Nagy’s greatest political rival from power, while those released from imprisonment and internment would be witnesses to his justice and supporters of his policy. With all this to gain, it seemed worth taking the risk of alienating some other supporters. One such was Mihály Farkas, whose responsibility for earlier illegalities ensured that he turned away from Imre Nagy again.

These considerations were recognized, of course, not only by the prime minister, but by his arch-rival, Rákosi, who made every effort to prevent and tone down this ‘rummaging in the past’ and ‘exorbitant pursuit of rehabilitation’. His position was made more difficult because the HWP Central Committee was also concerned to free the unjustly imprisoned communists. On the other hand, Rákosi could claim that the prime minister’s policy was undermining the credibility of the party leaders and even the party itself, which raised a danger that the socialist system might collapse. It was a help to Rákosi that the ÁVH, had retained its privileged position, which meant it could impede and obstruct the rehabilitations. Moreover the investigating bodies were still inclined to produce the evidence that the authorities wanted and expected to hear—evidence that did not besmirch the name of Rákosi or reveal the role that Soviet advisers had played in promoting the terror. The weightiest consideration was that the top leadership in Moscow was not pressing for a public investigation of those responsible, only for the release of the communists who had been condemned. So although Imre Nagy’s campaign achieved something (the release and rehabilitation of many communist detainees, including János Kádár), the most important case, the Rajk trial, was not reopened until 1956, and the reburial of the executed politician László Rajk did not take place until a few days before the revolution broke out.

Nonetheless, lightening the load of autocracy on the population was the most important achievement of the New Course. Although it was still possible to have a partial return to the pre-1953 economic policy after Imre Nagy was dismissed and aim again for rapid collectivization of agriculture, it was no longer possible to restore an atmosphere in which everything and everyone was imbued with fear and terror. It was not a case of Imre Nagy freeing the population from oppression, or releasing any politicians to the right of the Social Democrats. Indeed innocent people were still being condemned in political trials during Imre Nagy’s term as prime minister—among them Anna Kéthly, the Social Democratic leader of the greatest stature, in 1954. However, the ubiquitous fabric of terror had begun to fray.

The last, and perhaps least effective group of New Course measures were the reforms and ideas designed to refashion the structure of power. It was not by chance that Imre Nagy was condemned as anti-party in Moscow in January 1955. Of course in the original sense, so doctrinaire, committed and faithful a communist politician as Imre Nagy could not be anti-party. However, his ideas in the short term worked (or might have worked) against the party, though the intention was to restore the party’s lost prestige and ensure a communist political victory in the longer term.

From 1954 onwards, Imre Nagy was working to create an institutional, political framework for his New Course policy. An essential element in this was to break up the monolithic power of the HWP, by freeing government bodies from party control. That was the purpose underlying the creation of the Secretariat of the Council of Ministers, under Zoltán Vas and the Information Office of the Council of Ministers under Zoltán Szántó. The latter was supposed to ensure direct contacts between the government and the press and thereby the public, eliminating the party as an intermediary, but it also acted as a source of information for the government. Imre Nagy had the same motive in creating a popular front organization: to provide institutional frames for political activity by the non-party masses and given them a say in the country’s affairs. In other words, the front was to have been a government form that left room for a plurality of interests within the one-party system, through a relatively democratic structure. The danger of this was apparent to Rákosi and his supporters, who did their utmost to obstruct the foundation of a body that provided scope for political activity by the broad masses of the population. The debate crystallized, in the main, around two questions, on both of which Imre Nagy was defeated. He did not manage to ensure that individuals could be members, so that the front became simply an assembly of (social) organizations, which the party controlled in any case. He did not manage either to free the front from the party’s influence, so that it was left scarcely suitable for representing interests for which the party did not provide a framework. So the Patriotic People’s Front eventually founded on October 23, 1954 was no different from its predecessor. Effectively, it represented nothing and no one, and its main task became to conduct intermittently the single-slate local and national elections, which were of no concern to anyone.

|

| The founding congress of

the Patriotic People’s Front, held in Budapest’s Erkel Theatre on October 23,

1954 (MTI Photo) |

Equally unsuccessful were Imre Nagy’s attempts at the 3rd Congress of the HWP in May 1954 to alter the composition of the Central Committee and the Political Committee.

|

| Rákosi

delivers his report on May 24 to the 3rd Congress of the HWP, held on May 24–30, 1954

(MTI Photo) |

He managed to get Zoltán Szántó elected to the Central Committee, but his other candidates were defeated. Furthermore, the Secretariat headed by Rákosi gained stronger powers over the party.

Although the New Course had brought several important results by the autumn of 1954, the steps taken had not led to a breakthrough in any field. In each case the group behind Rákosi had successfully attacked and weakened the reforms, or at least threatened to do so. This meant that Imre Nagy’s policies were unable to satisfy those in Moscow who had initiated the changes, because the outcome of them was greater turmoil, not the order they had sought. However, it would be a mistake to blame this confusion simply on Rákosi’s efforts to counter them.

It is clear from the orders issued, the frustrated intentions and Nagy’s writings after his dismissal as prime minister that his ideas differed substantially from the role in which Moscow had cast him in 1953. The Kremlin had wanted the changes to bring peace and calm to Hungary. Imre Nagy, on the other hand, was aiming at a real reform of socialism and of the building of socialism. This meant breaking with all the mistakes that had been made in various fields. There had to be a return to the point where a false analysis of the situation had led the Hungarian party to depart from a political path that would have suited the conditions in the country and left adequate time for a transition. Imre Nagy wanted to turn the clock back to 1947–8. At that time there had still been outlets for various political interests, the rights of private peasant farmers, artisans and traders to own private property were still recognized in an only partly nationalized economy, there were no show trials against communists and former Social Democrats, and so on. If there had been the time and occasion to implement these reforms, the country might really have stabilized, but they certainly had a destabilizing influence temporarily. That meant Rákosi could present them in Moscow as surrendering the achievements of ‘socialist construction’. Imre Nagy was already being warned in the spring of 1954 to keep his reforms within the limits expected of him. So a policy that did not meet Moscow’s wishes was doomed to elicit a stronger reaction from the Kremlin sooner or later.

Another factor working against Imre Nagy and his New Course was the drift of international events. The Soviet-Yugoslav reconciliation was not going smoothly. Indeed there were no tangible results before Khrushchev’s visit to Belgrade in May 1955. Soviet-German relations were even more fraught. The Western powers restored sovereignty to the Federal Republic of Germany in the autumn of 1954, and drew the country into the Western economic and military system. (West Germany became a Nato member in May 1955.) So the Soviet efforts to create a single, neutral Germany were to no avail. This was seen in Moscow not just as a defeat, but as a threat, and caused the Warsaw Pact to be established as a response.

|

| András Hegedüs signs the founding document of the Warsaw Treaty, in Warsaw on May 14, 1955 |

Moscow’s dissatisfaction with the Hungarian prime minister’s policy and the foreign-policy reverses the Soviet Union was suffering were exploited successfully by Rákosi in late 1954. Returning to Hungary at the very end of November, after a long period of sick leave in the Soviet Union, he began at once to make use of the information he had gleaned there. On December 1, 1954, he informed the HWP Political Committee of the change in the Soviet position. Although the Political Committee did not withdraw its resolution of June 1953, it switched to identifying a ‘rightist’ deviation from communist doctrine as the main danger and condemning Imre Nagy’s policy. This was still too little for Rákosi. His aim was not just to gain a superior position relative to Imre Nagy’s, but to squeeze his political rival and his policy out of public life altogether. So he proposed that a party delegation should travel to Moscow to discuss the Hungarian situation with the Soviets. Imre Nagy opposed this (a stance that gave Rákosi a further argument for restricting his powers), but failed to prevent the consultation occurring.

Although the Hungarian party leaders arrived in Moscow with a detailed programme and several questions to raise, the agenda was dictated by the Soviet side, who were interested in only three things. The first, which received the least emphasis at the talks, was the state of the Hungarian economy. This was still not improving as the Kremlin leaders had hoped in the summer of 1953. They took a far more serious view, however, of an article written by Imre Nagy in Szabad Nép (Free People) on October 20, 1954. There the prime minister had advocated democratizing the party, castigated the errors caused by one-man rule, and called on party members to engage in active, independent political activity. Imre Nagy’s appeal was seen in Moscow as an invitation to indulge in factionalism directed against party unity, which was a serious crime. The Soviets were also incensed by Imre Nagy’s stubbornness. When outlining the situation in Hungary, Imre Nagy concluded that he could not work with the party first secretary, Rákosi, in a way that met the requirements of the New Course, which was perfectly true. Such a statement was tantamount to proposing that Rákosi be dismissed, so that Imre Nagy had trespassed onto a subject that was the province of the CPSU Presidium.

In spite of everything, Khrushchev did not recommend a complete break with the 1953 programme. All he pressed for was order in Hungary at last. Let the economic crisis be overcome, but in a way that would not run counter to the interests of socialism even temporarily, would not break up the agricultural cooperatives, or curtail investment in the arms industry (and heavy industry). The latter sector was the basis of economic activity and the former the main guarantee for the worker-peasant alliance. Let there be complete unity at the head of the HWP, with Rákosi’s leading role restored, although ‘the authority of Comrade Imre Nagy has to be safeguarded as well.’ So Khrushchev was offering Imre Nagy an opportunity to subscribe to the restored policy, admitting and condemning his own mistakes and in that case being allowed to remain in politics, if not in the front rank.

Attempts to restore the earlier system under new conditions

However, neither Imre Nagy nor Rákosi obeyed their instructions after they returned from Moscow. Rákosi was not content with his victory over the prime minister, whom he wanted to annihilate politically, once and for all. This was easier for him to do because Imre Nagy flouted the unwritten rules of Bolshevik discipline. Instead of accepting the criticism from Moscow unquestioningly, he tried to salvage some elements of the New Course and keep the situation under his control, at least to some extent. He was not prepared to exercise self-criticism or humbly and silently accept the new expectations of him. The HWP Political Committee led by Rákosi lined up behind the Soviet criticisms in condemning Imre Nagy, and set about drafting a resolution that would meet Moscow’s demands in full.

However, it was no longer possible in 1955 to pick up the reins of government where Rákosi and this team had dropped them in 1953. Neither the internal nor the external conditions were right for doing so. Although the opening up of Soviet foreign policy had suffered several reverses, international détente continued. On July 18, 1955, the great powers sat down in Geneva to negotiate, at the first summit meeting since the Potsdam Conference of 1945. In the autumn of the same year, the Soviet Union established diplomatic relations with the Federal Republic of Germany. Earlier in the year, the Austrian State Treaty had been concluded, turning Austria into a neutral country from which the Soviet occupation forces withdrew. Though Khrushchev was inclined to waver on some occasions and follow impetuously his momentary impressions on others, he was certainly working to remove some of the excesses of the Stalinist system.

Moreover, it was a different country that Rákosi came to head again after Imre Nagy’s reforms. Despite Imre Nagy’s refusal to exercise self-criticism, it was not easy to set him aside, let alone resort to the more radical means available before 1953. Hardly a year after the amnesties and the commencement of the rehabilitations it would have been impossible to try the prime minister and imprison him, although the possibility was discussed. It did not even prove feasible to dismiss him straight away. Although the resolution of the party Central Committee in March 1955 censured and denounced Imre Nagy’s policy, there were various domestic and foreign-policy reasons why Rákosi had to be content until mid-April with isolating Imre Nagy under virtual house arrest, using his real illness as an excuse. Not until three months after the Moscow talks was Imre Nagy progressively sidelined. First he was deprived of his party positions, then dismissed as prime minister (to be succeeded by András Hegedüs) and removed from his other posts, even his membership of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. His expulsion from the party came later still, in December 1955, while the Imre Nagy question—complete elimination of the political objectives he had represented—had not been completely resolved by the time the revolution broke out on October 23, 1956. The relegated prime minister, convinced he was in the right, was the one who tended to push for clarification of the situation in principle, writing incessant protest memoranda and polemics to the Hungarian and Soviet party leaderships. (These also circulated among a narrow circle of his political adherents.)

One factor of great importance, apart from Imre Nagy’s perseverance and strength of principle, was the change in the country’s atmosphere brought about by the New Course. Another was the increasingly well defined body of supporters which Imre Nagy had gathered around him by the end of 1954. Even at the onset of the New Course, during the Writers’ Union debate on October 23, 1953, writers who had been touring the villages in the previous weeks gave a report that stirred up an enormous debate, detailing the destruction caused by the HWP policy towards the peasantry. On that occasion, the one who came out most strongly against the government and in favour of the new political line was Péter Kuczka. The releases and the early rehabilitations in 1954 caused a crisis of conscience among ever larger groups of the intelligentsia (and party intelligentsia), as they confronted the gulf between the ideas they had believed in and reality. The self-examination that followed the crisis turned most Hungarian writers into advocates of the new political line. A succession of self-critical, revelatory pieces began to appear in the Writers’ Union newspaper, the Irodalmi Újság (Literary Gazette), in the autumn of 1953, written by Sándor Csoóri, Gábor Devecseri, Péter Kuczka, István Örkény and other authors. A circle began to form around Imre Nagy in 1954, consisting partly of colleagues and students, who helped him devise a radical reform of agriculture, and partly of politicians, writers and journalists. This group, which came to be known as the Party Opposition, remained faithful to the New Course even after the prime minister had fallen, taking upon itself, if need be, the attacks this elicited as well. However, Rákosi and his henchmen were unable to reproduce the terror prevalent before 1953. The sanctions imposed on the rebels against the official line could not be compared with the methods employed in the early 1950s.

The policy of Imre Nagy began to receive ever broader support in the Hungarian press during 1954. At the end of October, there was a stormy debate at a staff meeting of the Szabad Nép, which came out in support of the New Course and against the forces holding it back, which included the paper’s editors, as well as Ernő Gerő and Mihály Farkas. In November, support for the reform of socialism came from Miklós Gimes and later Géza Losonczy. They worked for another daily paper, the Magyar Nemzet (Hungarian Nation), which had just become the organ of the Patriotic People’s Front.

After Imre Nagy had been sidelined, those aligned with him suffered a succession of reprisals. Miklós Molnár, editor-in-chief of the Irodalmi Újság, was dismissed. There were several purges at the Szabad Nép: Péter Kende and Pál Lőcsei had to leave at the end of 1954 and Tibor Méray was among those ousted in April 1955. Yet it was all in vain. The journalists went, but the critical spirit remained. The press could no longer be forced to play the part it had been cast in before 1953. As the Rákosi group in power, intent on restoring the earlier order, tried to squeeze its opponents out of public life, the reform camp became stronger and stronger. In January 1955, the Kossuth Club, consisting of members of the intelligentsia, opened in Budapest, and it was on its premises that the Petőfi Circle was founded within the Union of Working Youth (Disz) on March 25, with Gábor Tánczos as its secretary. Although the Petőfi Circle did not become influential until after the 20th Congress of the CPSU, it then became one of the instigators and unifiers of the revolutionary demands, through its truthfulness, its sincere investigations of mistakes and crimes, and the public debates it held.

Meanwhile the releases from confinement continued, if not at the pace envisaged and planned by Imre Nagy. The rehabilitation of Noel Haviland Field, who had played a key part in the Eastern European show trials, caused the successive collapse of the false charges based on the testimony extorted from him. In Hungary’s case, this made it urgent to re-examine of the Rajk trial, but it remained taboo because of the part that Rákosi had played in it. However, Anna Kéthly was released at the end of 1954, followed in 1955 by Simon Papp, who had been sentenced in the Maort (Hungarian-American Oil Company) trial, and Cardinal József Mindszenty, followed by József Grősz, Archbishop of Kalocsa. On November 12, 1955, Béla Kovács, formerly general secretary of the Smallholders’ Party, was allowed to return with several associates from the Soviet Union. After the condemned communists, non-communist politicians and those accused in economic trials were successfully released or had their sentences reduced.

The 20th Congress of the CPSU, held on February 14–25, 1956

The 20th Congress of the CPSU marked a turning-point in the politics and ideology of the Soviet party and the international communist movement. Overturning the doctrine that a third world war was inevitable and proclaiming peaceful coexistence assigned new tasks to the leaders of the Soviet Union and its satellite countries. Although Khrushchev’s secret report revealing the crimes of Stalin was not to be published in full for 30 years, news of it began to spread immediately he read it out to selected party leaders. It confirmed the beliefs of those who had hitherto been opposed to Stalinism, and broke the resistance of many who had tried to stick by him.

The 20th Congress placed insoluble tasks before the Hungarian party leadership, which was still unchanged in composition. Rákosi was the one who had to head the Stalinization">de- Stalinization process in Hungary, unveil the mistakes and crimes of the past, and condemn the culprits (above all himself). Meanwhile he had to make sure that the top party leader (himself again) should not lose prestige. It is hard to imagine how the Kremlin overlords thought this could be done. Right through to the summer of 1956, they consistently urged that the most basic steps of de- Stalinization be taken in Hungary, in the other words that the resolutions of the 20th Congress be implemented, while continuing to support an unchanged party leadership, above all Rákosi. Nonetheless, the person responsible for the illegal acts committed had to be found, so as to vindicate the Soviets and the socialist system. As early as 1953, there were efforts to shift the whole blame onto Gábor Péter, who was already in custody. When this did not succeed, attention focused (after Imre Nagy’s dismissal) on Mihály Farkas. He was a suitable scapegoat because he actually bore some responsibility, and he had joined up with Imre Nagy in 1953. So denigrating him would serve as a warning to the apparatus, showing that those who adhered faithfully to the leader would come to no harm. However, it soon emerged that Farkas was not a significant enough figure for the purpose. Even before the 20th Congress, the question of Rákosi’s personal responsibility had been raised at a party meeting by József Szilágyi. At an activists’ meeting in Budapest’s 13th District in March 1956, György Litván, a grammar-school teacher, called for Rákosi’s resignation, even though Rákosi was there in person.

The Soviets, on the other hand, still stuck to Rákosi, for a number of reasons. For one thing they felt that a high turnover of personnel would further destabilize the leadership and the country. The changes since 1953 had already caused the Hungarian party enough trouble, and it was better to avoid another change in the party leadership if possible. For another, the Soviets saw in Rákosi a personal guarantee that Hungary would not adopt an independent policy of reform that might clash with the interests of the Soviet leadership. Finally, the Soviets failed to find in Hungary a person who met Soviet expectations and fitted the Hungarian conditions. When it finally became impossible, in July 1956, to retain Rákosi as first secretary, two possible successors arose on the Hungarian side, but there were serious objections to them both. János Kádár had been imprisoned under Rákosi, which raised his standing with Hungarian public opinion, but was a point against his election as party first secretary in Khrushchev’s eyes. His chances were also lessened because he had played a party in the trial and execution of Rajk (although not to the same extent as Rákosi), and there had been criticism of his political activity before 1945, especially the part he played in dissolving the Party of Hungarian Communists in 1943. A big consideration was that Imre Imre Nagy had earlier pressed for his promotion to the Political Committee, so that his election might be construed as a concession to the right. The other candidate was Ernő Gerő, who eventually became Rákosi’s successor. Nonetheless, it was obvious to everyone that he could not be a solution. He had been a member of the topmost leadership throughout the communist period and did not differ essentially from Rákosi himself, so that the public was just as strongly against him. The difficulty encountered with the succession is patent in one suggestion that was made: let there be no first secretary elected, let Political Committee members chair the meetings in turn.

While the Soviets saw no chance of dismissing Rákosi, the first secretary of the HWP busied himself obstructing both Hungary’s Stalinization">de-Stalinization and Soviet foreign policy. The historic reconciliation with Yugoslavia took place in Belgrade in 1955. This should have been followed by reconciliation between Yugoslavia and the satellite countries. Aware of what the Soviets expected, Rákosi was prepared to carry this out, although true to his colours, he missed no opportunity to criticize Yugoslav policy. Tito, however, was not prepared to be reconciled with the Hungarians except under adequate conditions with requisite guarantees. This contributed to making the Soviet foreign-policy initiative only half-successful. The sharp confrontation with the Yugoslavs ceased, but they did not return to the Soviet camp.

Growing support for reform, waning authority

The forces calling for reforms in Hungary gathered strength after the 20th Congress of the CPSU. This also applied within the party, where calls for real change and a radical renewal of the party became steadily more widespread. Nor was this confined to Budapest. Mobilization in the provinces became easier because many of Imre Nagy’s supporters were posted there as a punishment. For instance, József Kéri, who had been secretary of the party branch at the Council of Ministers while Imre Nagy was prime minister, was sent to Győr, as head of the prosecution service in Győr-Sopron County. Removing such people from the capital weakened the pressure there to some extent, but their presence had a strong effect on provincial opinion, helping to win people over to the reforms.

The mounting activity of the Petőfi Circle during this period began to give new direction and substance to the struggle against the Rákosi system. A few weeks after the 20th Congress, the Circle held its first large-scale, forward-looking event: a friendly meeting of former leaders of Mefesz (the Hungarian Association of University and College Unions), held in the Kossuth Club. A succession of professional debates began to take place in May, where more and more sensitive issues were discussed before swelling audiences. It became possible for historians (such as Domokos Kosáry) and philosophers (Georg Lukács and his disciples), who had been silenced, to appear in public again. Nékosz (the National Association of People’s Colleges) was socially rehabilitated. At a debate in the Central Officers’ Hall of the Hungarian People’s Army on June 18, Júlia Rajk, widow of the executed László Rajk, appealed publicly for her husband’s rehabilitation, while Szilárd Újhelyi declared the need to rehabilitate ‘a whole country, a whole people’. At an event styled a press debate, hardly a week later, the writer Tibor Déry ascribed the social problems to the structure of the system and spoke of the need for a radical transformation. Géza Losonczy apologized publicly for his past crimes, and the meeting called strongly for Imre Nagy’s return to power. Soviet Ambassador Yury Andropov included a description of the debate in his report to Moscow, saying he understood it had ‘essentially degenerated into a demonstration against the party leadership.’ This was more than the authorities were prepared to tolerate, especially as the next meeting was to have discussed the question of legality.

The Central Committee of the HWP, meeting on June 30, condemned the debates of the Petőfi Circle, which were suspended.

The Petőfi Circle moved, in several respects, beyond the previous polemics, which had remained within the party or at least a relatively narrow circle. Its role was not dissimilar to the one played by the protest pamphlets known as the cahiers, on the eve of the French Revolution, or by Kossuth’s newspaper the Pesti Hírlap (Pest News) before 1848, summing up the symptoms of crisis and stating the truth. The debates went beyond the cautious reforms and reformist formulations mooted so far, retaining only the two most important taboos: the stationing of Soviet troops in Hungary and the one-party system. The events brought into public life much wider groups than those who physically attended them. Audiences took what they had heard back to their work places and into the provinces, where the discussions continued.

Local forums of debate, modelled on Budapest’s, sprang up in several parts of the country, especially after a resolution of the Central Committee of the League of Working Youth in May had called for them to be established. The Zrinyi Circle in Kaposvár began to form in the spring. (Most of them were named after past writers or politicians with a local connection.) The convening of the Vasvári Circle in Szombathely more or less coincided with the June 30 resolution HWP Central Committee condemning the Petőfi Circle. The Batsányi Circle in Veszprém was headed by Árpád Brusznyai. The Petőfi Circle in Pécs, the Kossuth Circle in Debrecen (headed by Lajos Für) and several others followed in October. In other words, the Petőfi Circle made a big contribution to broadening and strengthening the support for reform. It took politics and criticism of the system if not out into the street, at least beyond the confines of the party, drawing much of the non-party population into political activity and debate about the future.

So the reform camp broadened, strengthened, united and clarified its programme after and in spite of the dismissal of Imre Nagy. Rákosi and his supporters, on the other hand, proved unable to handle the spreading crisis, and their half-measures simply only weakened their authority further. Removing Imre Nagy had not restored unity within the party. Throughout the period there were present, in the party leadership and all through the party organization, those who disagreed with the existing system, although they may not have gone so far as Imre Nagy in the changes they envisaged. They thought in terms not of reforming the system but of eliminating some of its excesses, above all of restraining its repressive apparatus, which had taken on a life of its own. The person who can be seen the main representative of this school of thought was János Kádár, but more and more people, even at lower levels in the party, were dissatisfied and likewise wanted to bring normality into the system. The leadership rejected these criticisms, dismissing all opposing opinions as right-wing deviations, as examples of Imre Nagy’s baneful influence, or as symptoms of ignorance and backwardness among the membership. Disciplinary, administrative proceedings were taken against the malcontents, who suffered various penalties, including exclusion from the party. However, the leadership did not dare to treat those high in the party in this way. Indeed Kádár became a member of the topmost body, the Political Committee, in July 1956.

As the real problems became ever more pressing, much of the party leadership’s time was still taken up with traditional routine tasks: addressing meetings of activists, visiting factories, and so on. Even less comprehensible is the way new problems were fabricated alongside the real ones. Lengthy, earnest debates took place, for instance, on such theoretical questions as how a former social democrat might turn into a communist.

The admission of West Germany to Nato had only stalled the process of international détente temporarily. It was no longer necessary to continue the forced pace of development of the army, or even maintain at its existing level what had been one of the moving forces behind the forced expansion of heavy industry. So the cuts in the army begun while Imre Nagy was prime minister could continue. This was facilitated by the loss of its all-powerful head, Mihály Farkas, for István Bata, the new defence minister, had nothing like the prestige needed to counter the efforts to cut down the forces caused by the economic problems. In the period before the revolution broke out, the manpower of the People’s Army was reduced in several stages, which aroused anxieties about their livelihood among the officers. They were also affected by the cuts, and the standard of living among those remaining service fell. To compound their difficulties, there were several practical shake-ups not directly related to the cuts.

One problem was that the authority of commanding officers was greatly undermined by the actions of intelligence officers reporting to the ÁVH, who often had greater power than their commanders. The helplessness against them felt by the field officers had much to do with the fact that after the revolution broke out, the army was reluctant and half-hearted in its cooperation with ÁVH units.

The morale of the enlisted men depended largely on the mood among the general public. After the respite of 1953, pressure began to mount again on the villages, where a noticeable fall in living standards followed the initial improvement. The discontent in the ranks was exacerbated by strict, often merciless treatment received in the army, their complete defencelessness against the officers, and the political manipulation, which was even stronger than in civilian life.

These circumstances greatly weakened the ability of the People’s Army to mobilize against any kind of foe. It was even less capable of suppressing any action against the existing regime, since the reforming ideas of the Petőfi Circle had gained ground, and officers were attending the debates with increasing frequency. This was wholly apparent to the military command and the party leaders, and also to the Soviets. Not long before the revolution broke out, a secret report was prepared for the general staff. This outlined the problems and concluded it could not rely on unconditional support from the army, in the event of a serious political challenge or test of strength.

There were similar uncertainties about how reliable the police were and how far they could be used against a possible disturbance. Its stability had been greatly undermined because it had been placed in 1953 under the same command as the state security forces, after the pattern in the Soviet Union. The idea had been that this would make the ÁVH less monolithic and bring it under tighter control and supervision. In the event, the ÁVH managed to retain its separate identity and power within the new joint divisional commands, which simply underlined its privileged position compared with the police. So it was no accident that Ernő Gerő was succeeded as interior minister by László Piros, an ÁVH general. Friction between the two forces became a daily occurrence. The ÁVH intervened several times in the affairs of the police, who were no less affected by the spread of reforming ideas than the army. More and more police officers sought changes and a real renewal. Though it was doubtless an exaggeration, there was some truth in the warning delivered in a report by Soviet Ambassador Yury Andropov: ‘The leadership of the Budapest police entirely supports Imre Nagy’s programme.’

Even the iron fist of the party, the State Office Authority (ÁVH) itself, faltered in the months leading up to the revolution. This is apparent, for instance, in a rising number of voluntary resignations, even though the strength of the ÁVH was sharply reduced at the beginning of 1956, which also caused serious dissatisfaction within it. Like the army, it lost a leader who had previously had absolute authority, and Gábor Péter’s conviction, only just before the revolution, brought further dismissals and arrests. (The Political Committee decided in August 1956 to prosecute several ÁVH leaders.) The constant threat posed to ÁVH officers by the rehabilitations, with increasingly frequent calls being made for the culprits to be named and prosecuted, alarmed and weakened the service. While their commanding officers were being sacked, many of those released from prison were returning to the political leadership, where they could be expected to press for the prosecution of those who had imprisoned and tortured them. At one Political Committee meeting in the autumn, János Kádár criticized both the ÁVH and Interior Minister Piros personally. Even the chief Soviet adviser in Hungary for interior affairs reported back to Moscow that ‘unhealthy feelings are spreading among some of the state security personnel as well.’

In the summer of 1956, the Soviet leaders decided the time had come for a further political intervention in Hungary. The situation was causing concern not only in the Kremlin, but throughout the socialist camp, where it was feared that ‘unexpected, disagreeable events might occur.’ The likelihood of this was increased by the rising at Poznań in Poland, where the security forces used arms to break up workers demonstrating for an improvement in living and working conditions. The clash cost almost a hundred lives, with several hundred wounded. To prevent any similar occurrence in Hungary, Anastas Mikoyan, who counted as a liberal member of the CPSU leadership, arrived in Budapest with a broad mandate to handle the crisis. Having gathered requisite information after his arrival, Mikoyan put forward two proposals for averting the crisis. One was aimed at restoring unity to the party and its leadership. Reversing Soviet policy hitherto, Mikoyan acknowledged that Rákosi’s dismissal was inevitable. He was relieved of his main functions on the grounds of ill health, but his merits were recognized and he remained a member of Parliament and the Central Committee. The idea behind Rákosi’s dismissal was to bring new blood into the party leadership. Then a new team, fully united in principle and practice, could set about addressing the most urgent tasks in line with his second proposal: to disperse the centres of opposition and end the opposition agitation and propaganda completely.

Far from solving anything, Rákosi’s predictable replacement with Ernő Gerő only made matters worse. The dismissal of the first secretary disquieted the groups for whom he represented a personal guarantee, while Gerő’s succession did nothing to win over those who were against Rákosi’s policies. Furthermore, Rákosi’s departure did not precipitate a purge of the party leadership. His cadres retained their positions, so that he could keep his hold over the top leadership. So the divisions within the Political Committee remained. Members were unable to reach a common position even on the most basic questions, so that responding to the challenges and resolving the problems remained impossible. Indeed larger and larger groups turned away from the leadership altogether. According to Andropov’s assessment in October 1956, ‘The Political Committee has no support either within the party or among the people ... they do not see any way out of the situation.’ In other words, it was becoming less and less possible to unravel the crisis and lead the country at all. The message from Gerő, transmitted through Andropov, was an open cry for help: ‘The situation in the country “is extremely serious and becoming worse,”’ he quoted Gerő as saying. One proposal for resolving the protracted and increasingly dangerous Imre Nagy question was to reinstate him in the party. For some time, however, the former prime minister would not cooperate in this unless the disputed issues were cleared up, in other words, unless he was allowed to retain his 1953 programme. In September 1956, Imre Nagy again refused to exercise public self-criticism, but at the beginning of October he was readmitted to the party nevertheless, even though the issues in dispute remained unresolved.

Nothing whatsoever came of Mikoyan’s second proposal. The attack on the centres of opposition was not even attempted. Even in the summer, shortly before his dismissal, Rákosi had concluded that drastic steps would not help, for if some individuals were arrested, others would spring up to take their place. The shaken leadership no longer had the will to take such measures.

Another reason why the domestic problems were set aside was the urgency of several long-neglected problems of foreign policy. During his three months in power, Gerő spent hardly a month in Hungary. He had to resolve the Yugoslav question, and ensure that Tito demonstrated the reconciliation by receiving him personally. This was no simple matter, because Tito did not disguise his dissatisfaction with the changes at the top of the Hungarian party and showed no inclination to meet Gerő at all. It took Gerő lengthy negotiations in Moscow to prepare for the event. Meanwhile Kádár, the second most powerful figure in the party, was absent negotiating in China. So the party and the country were left during a most difficult period without leaders capable or daring enough to take decisions.

The earlier tendencies strengthened again. Rebelliousness spread through the press. Mikoyan was already reporting in the summer of 1956, before Rákosi’s dismissal, how ‘power is tending to slip day by day from the comrades’ hands. A parallel centre of opposition elements is developing ... The press and the radio have escaped from the control of the Central Committee.’ The number of malcontents was increasing as well. The country’s resistance to the regime stiffened after Imre Nagy’s dismissal, with the return of forced rates of industrial growth and consequent restrictive economic measures and extra loads on society, borne mainly by agriculture again. The compulsory delivery quotas were increased and the conditions under which sales could be made on the free market were tightened. It was made harder for peasants to withdraw from cooperative farms. A new wave of collectivization ensued, combined with a redistribution of peasant holdings. Meanwhile industrial production norms and employees’ pension contributions were raised. The guidelines for the Second Five-Year Plan, released for public discussion, promised no improvement. Expert opinion rejected them, and the public realized bitterly that the leadership was still pursuing the earlier economic policies that had failed in so many ways. The living standard in 1956 was below its 1938 level, which had been far from prosperous compared with other European countries.

The housing situation remained critical. Many people were living in squalid shanties, and many others did not even have that. Most of those working on the priority, ‘socialist’ large investment projects had to live under inhuman conditions in communal huts. New industrial towns such as Sztálinváros and Komló became hotbeds of crime. The supply of goods there was worse than average, at a time when shortages and low quality were rife everywhere. The forced pace of the big investment schemes and the pressure on the villages greatly increased the number of people commuting long distances or taking jobs far from home, so that they spent most of the year in rudimentary hostels away from their families. Working conditions were poor and unhealthy. Frantic campaigns for higher productivity led to labour safety being neglected, so that industrial accidents were frequent.

The problems were compounded by the irrational pay structures. Wages were kept down to a minimum that precluded any rewards for qualifications or better quality work, which further increased the emphasis on quantity alone. On the whole, a semi-skilled worker doing a simple, repetitive job would earn more than the skilled workers and technicians who maintained the machinery or produced the prototypes. There were conspicuous pay differences between industries as well. Workers in heavy industry—the branches that were most favoured, such as smelting, iron and steel, and mining—earned several times as much as those doing equivalent jobs in the timber or textile industries. The situation was especially hard for young skilled workers, whose pay fell far short of the 1000 forints a month required for subsistence. According to a survey taken at the time by the National Council of Hungarian Trade Unions (Szot), over 50 per cent of families with three children lived below the bread line.

After a break of more than a year in 1953, the squeeze had returned, with the economic pressures stronger than before. The country realized ever more clearly that this was no way to live, and to varying extents people were aware there was an alternative, associated above all with the name of Imre Nagy. The opposition group that had formed within the party was joined, after the writers and journalists, by the rest of the intelligentsia, and in the autumn of 1956 by the rest of Hungarian society. The authorities showed they were weak and impotent. They lost the confidence of society, which had long found the system insupportable, and the barrier that fear had represented fell down. Society obviously did not want to live under the present system, which the authorities no longer had the power to defend.

On October 6, 1956, László Rajk and those who had been executed with him in 1949 were ceremoniously reburied in Budapest. Party leaders who spoke (Antal Apró and Ferenc Münnich) were followed a former co-defendant of Rajk’s, Béla Szász, who expressed the feelings of the crowd: ‘As hundreds of thousands pass by the coffins, they are not simply paying their last respects to the victims; they have an ardent desire and an unswerving resolve to bury an era.’ His words were not poetic licence. The system really did lie in ruins.

The first to demonstrate after the Rajk funeral were students, who marched through Budapest on the same afternoon, shouting anti- Stalinist slogans. While the party leaders remained on the old path, travelling to meet Tito and demonstrate their reconciliation, the students struck out in a radically new direction. An assembly in Szeged on October 16 decided to withdraw from the Union of Working Youth (Disz) and reconstitute of Mefesz, the students’ association. University students from all over the country had joined it by the time the revolution broke out on October 23. This development was not just a stage on the road to revolution, but revolutionary in itself. A self-governing organization was being founded in a country where nothing had been allowed to function independently of the party. The Mefesz membership elected its leaders independently, without giving the HWP an opportunity to put up nominees. A specific group of young people had formed body to represent them as a stratum, which ran counter to the official ideology, which denied that differences of interest still existed in a socialist society.

The student assembly held at Budapest Technical University on October 22, 1956 went still further. The meeting decided not only to join Mefesz, but to formulate demands, influenced by the events in Poland. A demonstration of solidarity with the changes in Warsaw was announced for the next day. In a break from the usual formalities, what they addressed to the party was not a petition, but a set of demands, reinforced by a street demonstration. Their Sixteen Points no longer observed the taboos that the Petőfi Circle had respected in the spring. Their demands included the withdrawal of Soviet forces and restoration of a multi-party system. Neither the press nor the radio would publish their demands in full and the students ruled out any abridgement. So they made stencilled copies instead, which they distributed on the streets, pasted on walls, and sent with delegations to the Budapest factories.