Hungary before 1914 had been an integral part of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, which was a medium-sized power in Europe. This meant that without being an independent nation-state, Hungary had the constitutional power to determine its own internal affairs. After the First World War and the peace settlement of Trianon of 1920, it regained full independence, but lost two-thirds of its territory and half its population, including several million Hungarians along with other nationalities. This turned Hungary into a small nation-state. Revolutionary attempts at modernization in 1918-19, first democratic and then communist, failed to overcome the national catastrophe brought on by the military defeat. Domestic support for the communist approach, never very great, was soon dissipated. Political life and thinking in Hungary between the two world wars came to be dominated by the demand for territorial revision. Socio-economic modernization became associated with the revolutions, which were unjustifiably blamed for Trianon was unjustifiably blamed, so that the idea of modernizing society and the economy became sidelined until the 1930s. By that time, only fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were able to offer diplomatic (and in the latter case economic) support for Hungary´s desire to regain territory. This line of policy was bitterly opposed by the advocates of democratic transformation, but the political elite gave priority to revision and took the country into the Second World War on the side of the Axis. The great Hungarian historian and political thinker Gyula Szekfű , called the quarter of a century between the wars a `Neo-Baroque coagulation´; of the pre-war system. This rigid system lurched to the right in the later 1930s.

Nonetheless, the need for political, economic, social and mental overhaul began to cause mounting concern in Hungarian political and public life in the early 1930s, as the ripples of the Great Depression were felt. The notions of addressing the peasant question through land reform, on the agenda since the end of the First World War, were reinforced by the depression and later by the outbreak of the Second World War. For it was clear that post-war Hungary would be a different place. Furthermore, the global scale of the war made it clear that a decisive influence on Hungary´s fate would be exercised by whichever superpower brought Central and Eastern Europe under its control.

Many ideas about the character of the emerging system and the tasks it would face arose immediately before and during the war. Naturally, different strands of opinion—the conservative-liberal Pál Teleki (prime minister in 1939-41), Gyula Szekfű, the liberal democrats, the plebeian democratic Independent Smallholders´ Party, the Social Democrats , or the Third Way `populist´ members of the intelligentsia-made different recommendations. But there was a remarkable degree of conformity about the main issues. Everyone agreed that the political structure needed changing. Its autocratic features had to be curbed and its democratic institutions given greater substance. The idea of social justice and the social or even socialist idea of welfare policy needed bringing to the fore. The system of public administration needed democratizing. The anachronistic system of landholding needed altering, through a radical or more limited land reform. The economy required overall modernization. Here a seminal factor would be an economic policy of active state intervention, direction and even planning. Reform was called for in the system of public education, and so on. It was also agreed that the national grievance of Trianon and its truncation of the country´s territory should be remedied in some way, by revising the borders set after the First World War (or at least regaining areas with an overwhelming Hungarian majority), or through close cooperation among countries and peoples in the region, perhaps going as far as confederation. Only the small underground Hungarian Communist Party saw any need for a Soviet-style transformation.

Disregarding the Communists, there was a consensus that Hungary should withdraw from the war by concluding a separate peace with the Western allies, mainly to conserve its military and economic power for the post-war settlement period. This idea became unrealistic as the Soviet forces advanced. Only after Romania had bailed out of the war in August 1944, when Soviet forces were already fighting on Hungarian soil, did the country´s leaders turn to the Soviet Union. However, any idea of Hungary bailing out had to be abandoned on October 15, 1944, when there was a coup by the Hungarian Nazi Arrow-Cross movement and the governor or regent, Miklós Horthy, was removed from office. Hungary´s attempt to withdraw from the German alliance had failed at the last moment when such a move could still have exerted any influence over the country´s position after the war.

These domestic aspirations to modernize and those who represented them had little direct influence on the arrangements actually made after the war. Many prominent figures (such as the third-way advocate Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky of the Smallholders´ Party and the Social Democratic theorist Illés Mónus) perished in the war or the Nazi terror. The ideas of those who remained became discredited. The failure to bail out of the war precluded even the smallest amendment to the Trianon peace in Hungary´s favour. Even a partial correction of some Trianon injustices might have helped to offset the mental trauma of the wartime cataclysm and given the new democracy untold legitimacy. The Hungarian armistice agreement of January 20, 1945 declared that the pre-1938 borders had to be reinstated, but leeway was left in Transylvania for the retention of certain reannexed areas. That last hope was dispelled by the peace treaty . Hungary found itself in a uniquely disadvantageous position. The leaders of all the other subsequent Soviet satellite states could argue that with Soviet intercession, they were `giving the people a national gift´. (The Romanians received Transylvania, the Czechoslovaks the national sovereignty and territories taken from them under the 1938 awards, the Poles Eastern parts of Germany and Danzig, and the Bulgarians part of southern Dobrudja. However, they all suffered grave territorial losses at the same time, notably the Poles.)

The fate of Hungary was decided primarily by the Soviet Union and only secondarily by agreements among the Allied Powers or ideas held by the surviving domestic political forces. The three great powers constituting the anti-fascist alliance - the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom - appeared to agree that the new Europe should consist of independent states with a democratic form of government. Soviet great-power policy was devised by Stalin, as a victorious military commander and leader of a world power.

|

J.V. Stalin in about 1950 |

He was presumably aware of that the latent tensions in the anti-fascist alliance would soon come into the open. Although he thought that another war, with the West, could be avoided, he was afraid of the prospect, and the Soviet economy, ravaged by the war, could well have done with Western capital for reconstruction, especially from the United States. Of the two great factors governing Soviet foreign policy - security of the country´s borders and its world revolutionary mission - Stalin gave priority to the first. The Soviet Union set about gathering the smaller countries of Central and Eastern Europe into alliances of `friendship´ and military and economic subordination. Stalin´s general idea was to retain the territories and spheres of interest gained in 1939-41 under the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and win Western acceptance for doing so. Hungary lay on the periphery of this sphere, so that it was not central to Soviet aspirations. Moscow wanted to see in Budapest a ´friendly´ coalition government based on the principles of the anti-fascist popular front proclaimed at the seventh congress of Comintern in 1935 and pursuing a foreign policy friendly to the Soviet Union. Hungary could not even reckon on receiving part of Transylvania, which would remain with the likewise defeated Romania. There had been earlier Soviet plans, for instance for an independent Transylvanian state, mooted in 1941-43 and in the one comprehensive Soviet peace plan, framed in a memorandum by Deputy People´s Commissar Ivan Maisky in January 1944. But these sought to divide, rather than dispense justice or reflect settlement proposals purportedly favourable to the Hungarians. They assumed that the anti-fascist alliance would continue and aimed at an ostensibly democratic transformation of the systems of former enemy countries. The last objective was enunciated also in the Yalta ´Declaration on Liberated Europe´, endorsed by Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt. The Soviet Union set about creating in its sphere of influence so-called democracies that formally complied with the democratic principles formulated at Yalta. However, the Soviets were not really guided by the principles of political choice, political freedoms and popular representation. The overriding concern was to further the interests and security of the Soviet empire. In Hungary´s case, it seemed unlikely that Stalin would support a complete communist take-over once the war was over, but he was expected to insist on the local communist party obtaining essential positions of political power.

The series of negotiations to prepare for creating a new political centre in Hungary took place in Moscow in October to December 1944, formally as a continuation of the ceasefire negotiations held with Governor Miklós Horthy. They were not even attended by two important potential participants: the Hungarian democratic progressive forces and the Anglo-Saxon powers, with whom the former had been trying to make contact during the war. While the initial stage of the negotiations was taking place, Churchill and the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, gave Stalin an almost free hand under the famous `percentage deal´, despite American misgivings. This arrangement divided Central and Eastern Europe into Western and Soviet spheres of influence. Greece was to join the Western sphere, while Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria came under the Soviets and Yugoslavia was shared equally. The leaders spoke of the agreement among themselves as having temporary validity, but the division was to prove robust.

The delegation led by Gábor Faragho, sent to Moscow to negotiate on Horthy´s behalf, consisted of high-ranking military officers and politicians. They had few ideas about the future shape of Hungary. Furthermore, they no longer had the backing of Horthy and the state after the coup by Ferenc Szálasi´s Arrow-Cross movement. The Hungarian communist leaders in exile in the Soviet Union had relatively strong ideas in principle, but were uncertain about what practical steps to take. Their discussions on a practical programme in September 1944 outlined a fairly clear plan of action that omitted all but a few elements of revolutionary radicalism. There would be a democratic political structure with a coalition government, but the question of the Communists´ share and weighting in that government was left open. However, the plan noted points where the bourgeois democratic structure might be `exceeded´ (the so-called `national committees´ to run local government and the land reform) and some where it was vital for the party to gain positions (the police and public administration).

Another strong influence on how the new Hungarian system developed came from the direct military and tactical interests of the Soviet Union. Greater emphasis was placed initially on elements of continuity with the pre-war system, as the Soviet military command and Stalin himself still hoped that the Hungarian state and army would change sides. The Soviets greatly overestimated the military and political weight of the Horthy delegation and negotiated with them almost exclusively, even for some weeks after the coup of October 15, 1944. Only when it emerged that the Hungarian forces were still fighting, despite the appeals of generals Béla Miklós and János Vörös, did they change course, turning down Miklós´s request to be allowed to return to Hungary and negotiate with Hungarian political forces on forming a government. On the other hand, they then allowed the Hungarian Communist leaders to begin organizing their party and the National Independence Front (the kernel of the later coalition).

At the end of the negotiations, the Communists, returning temporarily from Hungary, and the Soviet leadership (with the cooperation of Molotov and Stalin) prepared together the basic features and documents for the new system of public law. The night of December 5, 1944 was the one occasion on which all three sides met together. However, the former delegates simply had to endorse the founding documents and the consistency of the Provisional National Government. Colonel-General Béla Miklós became its head, its members being chosen from the former ceasefire delegation, democratic politicians from liberated areas, and Hungarian Communists from the emigré community in Moscow.

The establishment of the new political centre meant that the legitimacy of the previous Hungarian state was not recognized and a new fount of law was created in its stead. The Communists dominated the process of organizing national committees, and in some cases, people´s assemblies in the Soviet-occupied parts of the Trans-Tisza and Danube-Tisza regions. These bodies ostensibly elected (but actually appointed) the members of the Provisional National Assembly. They were drawn from parties and organizations participating in the Hungarian resistance: the Hungarian Communist Party (HCP), Social Democratic Party, Independent Smallholders´ Party, National Peasants´ Party, Citizens´ Democratic Party, trade unions, etc.

|

The Provisional National

Assembly in Debrecen, in the oratory of the Reformed College |

The first four of these were also represented in the government, which came together as a broad, grand coalition of all the political forces active at that moment. This arrangement, incidentally, was more or less general in Central and Eastern Europe at that time. Defeated Romania and Bulgaria and formally victorious Poland alike were placed under `new democracies´ similar to Hungary´s, which were soon being referred to as `people´s democracies´.

A `people´s democracy´ was a political structure that furthered Soviet security needs and the requirements of the Yalta declaration. The former was provided by the parliamentary and governmental preponderance of the local Communist parties that Moscow had ensured, along with Communist occupation of certain essential posts (primarily in interior affairs and public administration). The latter was met by the still-provisional coalitions, which gave representation in political life to all democratic parties. The system that applied in Hungary from December 21, 1944 until the elections of November 4, 1945 fully complied with the Yalta criteria. The construct of a `people´s democracy´ held open the possibility of transferring to a Soviet-style system, although in Hungary´s case, this was referred to as something uncertain that might occur in the future. On December 5, 1944, Stalin underlined as a general guideline the independence of the Hungarian Communists, but warned them against excessive speed. As he put it, `You need not be sparing with words but you should not scare people either. Then, once you have strengthened, you can go further.´ The Provisional National Assembly did not do anything substantial except elect the government and endorse the repeated request for a ceasefire. The Provisional National Government received broad powers to govern by decree. The unrepresentative nature of this legislative body (with a preponderance of Communists and Social Democrats) and its questionable legitimacy (resulting from the irregular way in which it had been chosen) seemed natural under the exceptional, wartime conditions.

The task of the coalition government was made easier because there was no real difference of opinion among the parties about the most urgent tasks and decisions. The Communists were the quickest to set about building their party, thanks to effective support from the Soviet army. In domestic affairs, the HCP political programme (`Three-Year Plan for the Rebuilding and Advance of Hungary´) promised a bourgeois democratic, parliamentary system, with respect for freedoms and an end to discrimination (the laws against the Jews). In foreign affairs, it proposed turning against Nazi Germany and joining the Allies, pursuing reconciliation with neighbouring countries and maintaining friendly relations with the Soviet Union. In economic affairs, it envisaged an extensive land reform with compensation to former owners. There was to be freedom and support for private ownership and private enterprise, major moves to protect consumers, and modern welfare policies. These ideas united not just the Smallholders´ Party, the Social Democrats and Peasants´ Party, but all politically minded people, apart from fanatical adherents to the Arrow-Cross.

However, the ideas of the political parties differed more sharply over the prospects for the future. The operation of the fascist parties was to be prohibited, of course, but the governing party of the Horthy era was not to be allowed to re-establish itself either. Some of the conservative and liberal politicians of the inter-war period left the country. István Bethlen was taken off by Soviet troops.

Most of those who remained swelled the already heterodox ranks of the Smallholders´ Party. This became the home of many ideas about short and longer-term political objectives. The common factors were a Western, bourgeois, liberal type of political system, an agrarian emphasis in economic policy (centring it on Hungarian agriculture), and good relations with the Soviet Union, but basic accordance with the Western, Anglo-American alliance. This group of ideas was espoused by the centre of the party, headed by Zoltán Tildy, Ferenc Nagy, Béla Varga and Béla Kovács.

|

Béla Varga, speaker of the National Assembly, addresses the assembly of the Independent Smallholders´ Party (FKgP) |

The conservative wing (people like Gyula Dessewffy, Dezső Sulyok and Zoltán Pfeiffer) stood closer to the `Christian-national´ ideas current between the wars. The left-wing radicals (István Dobi and Gyula Ortutay) believed in allying with the Communists and Social Democrats and breaking with the old system in as many respects as possible. The supporters of the Smallholders´ Party were extremely varied socially as well. Most belonged to the landowning peasantry or the urban middle class, but they included many others who had been associated to some extent with the old system and looked upon the uncertain future with anxiety.

The Social Democratic Party was likewise divided. According to its main watchword, the party was fighting for `Democracy Today, Socialism Tomorrow´, both of which were to be attained gradually, above all through democratic, parliamentary struggles. All kinds of revolutionary approach were rejected. The influential political figures in the centre of the party (Antal Bán, Vilmos Bőhm, Anna Kéthly, Károly Peyer, Imre Szélig and Ferenc Szeder) stood close to the Smallholders. However, the Social Democrats wanted more state intervention in the economy and a strong welfare policy rather than agrarianism. They also sought a Western orientation in foreign policy, but in educational and cultural policy, they differed from the Smallholders´ Party in advocating consistent secularization-separation of church and state. The so-called left wing of the party, headed by György Marosán, was in dispute with the centre mainly about close cooperation with the Communists. The man who headed the Social Democratic Party, Árpád Szakasits, did not present a decisive political profile and stood balanced between the two wings in most respects. The party´s voters came mainly from the skilled workers and lower middle classes.

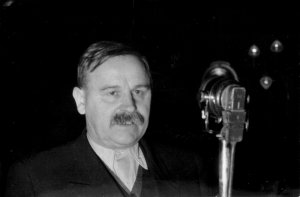

|

Árpád Szakasits |

To the consternation of some of its old supporters, the HCP proclaimed in public a kind of `left-wing social democratic´ programme. They silenced the calls in their ranks for `proletarian dictatorship now´ and presented themselves as the firmest advocates of the new Hungarian `people´s´ democracy. They did not deny the distant prospect of socialism, but they proclaimed it even less than the Social Democrats. They pressed for a strong state role and intervention in all fields of the economy. In foreign policy, they plainly and openly urged orientation towards the Soviet Union as `liberator´. The core of Communist leaders who had returned from Moscow were less concerned with open political debate than with acquiring political positions, especially key positions of state power-leading posts in the police, state security and public administration. The ultimate aim of the HCP remained to Sovietize the country, but this was kept secret for the time being. In fact, both the returnee leaders, mainly from Moscow (Mátyás Rákosi, Ernő Gerő, Mihály Farkas, József Révai and Imre Nagy), and the cadres from the illegal movement at home (László Rajk, János Kádár, István Kovács and Gábor Péter) were convinced that only a Soviet-type system would do. The Communists soon had widespread support among the urban working class (especially the less skilled of them), the rural poor and the intelligentsia. The HCP won over many of those of Jewish origin who had survived the war, but it also took into its ranks many former supporters of the extreme right wing. (The latter became known as the `little Arrow-Cross´.) Support also came from people who did not agree with its policies at all, but for one reason or another, thought the future lay in the Communists´ hands. The Soviet military authorities gave the HCP special support. There were communist sympathizers operating in every other party, even at the highest level, some of whom secretly joined the HCP (the crypto-communists).

The National Peasants´ Party was based as a political force on the pre-war ideas of the populist writers´ movement. This made for an eclectic set of policies that were agrarian and centralist, yet expressly Third Way and anti-capitalist. The party´s main concern was to develop Hungarian agriculture. Its adherents envisaged a social system grounded on the smallholder peasants who had just obtained land, coupled with an active role for the state. There was strong emphasis on the national character of the party, in which extreme anti-German views also appeared. For instance, the party was pressing for the deportation to Germany of the whole German minority in Hungary. Many members of the public saw the National Peasants´ Party as an auxiliary party to the Communists. Indeed, there was a similarity of position in several respects, although many leaders (including Imre Kovács and Ferenc Farkas, and also István Bibó, who took part in shaping the party´s image) were strongly opposed to Sovietizing the country.

|

Péter Veres |

Most leaders of the National Peasants´ Party were writers and intellectuals with little practical political experience. (It was headed by Péter Veres. Also prominent were József Darvas and Ferenc Erdei, and the poet Gyula Illyés for a time.) Its electoral support was drawn mainly from the poor peasantry and the provincial intelligentsia.

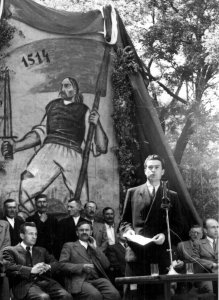

|

The presiding committee of the National Peasants´

Party (NPP) at a celebration in Cegléd of the peasant leader György Dózsa (d. 1514). The speaker is Imre Kovács. Behind him, from the left, are József Darvas, Péter Veres and Gyula Illyés |

The Citizens´ Democratic Party led by Béla Zsolt had been the haven of the liberal opposition under the Horthy regime. It attracted advocates of classic Western democracy, for whom the Smallholders were too nationalistic, clericalist and agrarian. The Hungarian Radical Party was intent on continuing the bourgeois radicalism once associated with Oszkár Jászi. These two parties, much smaller than the four mentioned previously, drew support from the petty bourgeoisie and intelligentsia in the cities, especially Budapest.

The political parties had about an aggregate membership in the millions. (The Smallholders had 900,000 members in the summer of 1945, the Social Democratic Party 350,000, the HCP 300,000, the National Peasants´ Party 200,000 and the Citizens´ Democratic Party 50,000.) Outside the parties, a significant political role was played by the trade unions, which were associated traditionally with the Social Democratic Party. However, the Communists began in 1945 to gain ground steadily among the union leaders, until the two parties eventually agreed to divide the union positions equally.

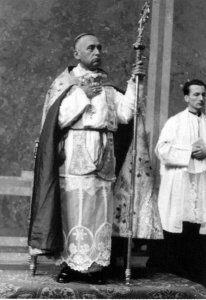

The churches were also a significant factor in politics, especially the Catholic Church, which was the largest. In 1945, Pope Pius XII appointed as [?& prince-primate and archbishop of Esztergom] József Mindszenty, hitherto bishop of Veszprém.

|

The consecration of József Mindszenty as archbishop of Esztergom. |

The new head of the Catholic Church had resisted the Arrow-Cross movement in the closing months of the war, but he held conservative, legitimist (royalist) views. He was distrustful of the institutions of democracy and strongly opposed to the Communists. No strong, separate Christian political party developed in 1945. Mindszenty gave no support to the Democratic People´s Party of István Barankovics, with its Christian socialist and strongly democratic platform, placing his hopes in the composite Smallholders instead.

The mass mobilization of Hungarians into political activity signified an effort by society to recover from the great shock of 1945 as soon as possible. There had been air raids, German occupation, daily experiences of hitherto unprecedented total war, a front line that took more than six months to plough across the country, and a reign of terror under the Arrow-Cross. After the fighting came pillage and violence by the Soviet occupation forces, which forced the population to its knees.

|

The blown-up Margaret Bridge in Budapest |

In the spring of 1945, there were absent from the country the many Jews deported and killed in the extermination camps, the prisoners of war taken by the Soviets, the soldiers and civilian refugees who had retreated westwards with the Germans, and the tens of thousands removed by the Soviet occupiers to forced-labour camps. Meanwhile the new occupiers were followed by hundreds of thousands of Hungarian-speaking refugees from Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia, who had left their homes to escape reprisals from the restored authorities in neighbouring countries. Despite the ghastly human, material and moral costs of the war, the chance of eginning again inspired even those who were otherwise cautious or pessimistic about the Soviet occupation.

|

Postal services resume: a postman delivering to a ruined house |

The public, almost without exception, rejoiced that the war was over, but saw it more as a relief (from anxiety and fear of death) than a liberation. Most people appreciated the new freedoms in public life and institutions of democracy, and played an enthusiastic part in clearing up the ruins and bringing the country to life again. However, they feared the unknown and the prospect of the Communists taking over power.

|

Clearing away rubble in the Buda Castle district |

On January 20, 1945, the Hungarian Armistice Agreement was signed by a delegation headed by Foreign Minister János Gyöngyösi, sent to Moscow by the provisional government.

|

Foreign Minister János Gyöngyösi signs the armistice agreement in Moscow. On his left is Soviet Foreign Minister V.M. Molotov, and behind him Hungarian State Secretary István Balogh |

The Hungarian administration and armed forces were to retreat behind the borders of December 31, 1937. All the territorial gains made towards the end of the Horthy period were lost. An Allied Control Commission (ACC) was to monitor the work of the new government. Although all the Allied great powers were represented on the ACC, everything was decided in practice by its Soviet chairman, Marshall Kliment Voroshilov. Under the armistice, Hungary was to pay US $300 million in reparations, which was a sizeable economic burden on a country devastated by the war. However, Hungary ceased to be a hostile country and its international isolation eased to some extent.

Hungary remained a kingdom for the time being (up to 1946) and there was no change in the system of public administration, at the express request of the Soviet military authorities. However, the local representative bodies were `re-elected´ under the post-war emergency conditions by national committees drawn from the political parties. So the ostensibly direct, democratic measures by the central administration and new state authorities were controlled and often overruled by national committees reflecting the party consistency of the coalition, until these were swept aside after the complete liberation of the country.

The armistice required Hungary to join in the war against Nazi Germany, but little progress had been made with mobilization before the European war ended. Despite the agreement, the Soviets were reluctant to release prisoners of war into the Hungarian army. The two divisions organized only served behind the lines on policing duties in Austria. Greater speed went into reorganizing the police force, which remained the most important armed force in the years that followed. The HCP immediately occupied the salient positions in the Ministry of the Interior and the police, whose organization it treated almost as an internal party matter.

The government set about the twin tasks of restoring the economy, which had almost been paralysed by the war, and the system of public administration. The situation was made much more difficult because pillaging of the country continued, even after the war damage and the German and Arrow-Cross depredations were over. The Soviets plundered and shipped home any German goods they found and rounded up tens of thousands of civilians, who were sent to prisoner-of-war and labour camps. They also placed the production equipment that still functioned at the service of the Soviet war machine. There were severe difficulties with public supplies, especially to the cities, while strong currency depreciation and price inflation set in.

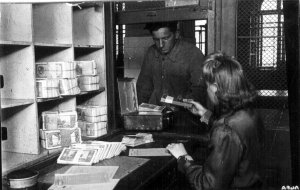

|

Galloping inflation : paying out money |

The new government did relatively better in two other important fields. On March 17, 1945, a decree on land reform was issued, based on schemes devised jointly by the Communists and the National Peasants´ Party. A well-organized central campaign and cooperation with local claimants led within weeks to the confiscation and redistribution of land belonging to those declared to be traitors and to former members of the Arrow-Cross and the Volksbund. Also taken over (with a promise of compensation) were large and medium-sized estates of over 100 cadastral hold (57 hectares) and peasant holdings of more than 200 hold (114 hectares). These measures allowed about 3.3 million hold (1.9 million hectares) to be distributed among 650,000 claimants.

|

Land redistribution in Újpest |

Efforts began early in 1945 to bring war criminals to justice, through a system of people´s prosecution departments and people´s courts set up by the government. The people´s courts alone sentenced 27,000 people for greater or lesser crimes in the coming years, of whom 190 were executed. However, there were no lynchings or kangaroo courts. Screening committees were also set up, to examine the pre-war and wartime political record of public employees.

|

The bodies of Ferenc Szálasi, Gábor Vajna, Károly Beregfy and József Gera on the gallows at Markó utca Prison in Budapest, after their execution for war crimes |

The German forces were expelled completely from Hungarian territory by April 1945. The Provisional Government moved from Debrecen to Budapest, and the war ended in the following months, at least in Europe.

|

Prime Minister Béla Dálnoki Miklós address the first Budapest meeting of the Provisional National Assembly |

The time had come to replace the provisional arrangements with a permanent structure, covering domestic and foreign affairs. At home, this meant holding parliamentary and local-government elections and enacting a new constitution and basic laws. Diplomatic normalization called for a peace treaty and other international agreements, so that the country could reintegrate into world affairs.

It was also urgent to hold parliamentary and local-government elections because the legislature of 1944-5 had resulted from irregular elections. (The biggest party in the Provisional National Assembly of December 1944 was the HCP, with 38 per cent of the seats, while the Smallholders held 25 per cent. The representatives of the newly liberated areas invited to join in the spring of 1945 were chosen according to proportions agreed among the political parties themselves.) The relative strengths shifted further towards the Communists and the left wing when the Provisional Government was reshuffled in July 1945. These matters were raised by the Western powers on several occasions, citing the Yalta principles. They also protested strongly, in the summer of 1945, against the Hungarian-Soviet economic agreement, for flouting the principles of free trade.

Rákosi raised the question of elections at the beginning of May 1945. He argued that the Communists had no need to fear them: `If we do them well, they will show a colossal Communist-Social Democrat victory.´ He still had no doubts early in July that the Communists in conjunction with the Social Democrats could gain a majority. At the end of August, he thought that the Communist-Social Democrat majority in Budapest would be `70 per cent, perhaps more, perhaps less.´ These optimistic forecasts clearly reached Moscow. Although they were offset by other, more realistic assessments, they certainly had an influence and the Soviets did not deal much with the questions of a later election `bloc´. According to Rákosi´s reminiscences, `Stalin recommended over the elections that there was only one possibility: for the parties of the Independence Front to agree to split the seats and put up a common list. On the one hand, this would prevent the election agitation becoming inflamed and alleviate the uncertainty of the leap in the dark that the election meant under such conditions.´ The Soviets would have liked to see `people´s democracy´ instead of democracy in Hungary, but without inciting conflict with the West.

The HCP also wanted a joint list, but only with the Social Democratic Party, since it believed there would be a victory for itself and the workers´ parties in general. Local-government elections were held in Greater Budapest in October 1945, as a dress rehearsal for the general elections. The leadership of the Social Democrats agreed to a common list with the Communists only after heavy debates and infringement of the principles of intra-party democracy. Against that background, it was not surprising that more than 50 per cent of the votes went to the Smallholders´ Party, while the so-called Unity Front received only 43 per cent

At this point, the Soviet leadership, misled by the Hungarian Communist optimism, came to its senses. Voroshilov, chairman of the ACC, proposed on Stalin´s orders that the four parties of the government coalition should run jointly in the general general elections and agree in advance on a division of the seats. The heads of the Hungarian political parties came under serious pressure to comply. Voroshilov was willing to assign almost half the seats (47.5 per cent) to the Smallholders. Eventually, the formation of a joint list and an election bloc was prevented by Western protests and interventions by the rank-and-file and leaders of the Smallholders´ Party. The ACC and the Soviet Union then consented to regular elections being held, rather than let the Hungarian issue put cooperation with the West at risk.

The parties of the National Independence Front then agreed to retain a broad coalition government, but they stood separately in the National Assembly elections on November 4, 1945. Under the most democratic electoral system in Hungary´s history, almost 5 million citizens cast their votes for regional party lists. The franchise extended to all citizens over the age of 20, except for war criminals and members of the dissolved fascist parties and the pre-war right-wing parties, irrespective of sex, property or level of education. The results were as follows:

The results were as follows:

Independent Smallholders´ Party 57,0 %

Social Democratic Party 17,4 %

Hungarian Communist Party 16,9 %

National Peasants´ Party 6,9 %

These parliamentary elections immediately altered the political situation in Hungary. The various political forces in Romania, Bulgaria, Poland and Yugoslavia had stood as an electoral alliance or bloc, in what was more a voting exercise than elections. In Hungary, on the other hand, there had been real elections. Despite the prior declaration by the parties that the coalition government would remain regardless of the results, the provisional government gave way to a legitimate coalition based on relative strengths in Parliament, although the consensus on the tasks before the country meant that it was still a grand coalition. Hungary was on the periphery of the Soviet sphere of influence, within which there was still some differentiation. However, its position was still an intermediate one, outside the group of countries in which free elections were essential. Moscow in the coming years was to find clear fault with the Hungarian Communists and Rákosi personally, for allowing the elections to take place in this fashion.

The elections results showed that the Hungarian public wanted to be active in influencing its own destiny, for the turnout was over 90 per cent. The voting pattern reflected general agreement that there should be some kind of change. It can be assumed that most Smallholder voters did not seek any persistence of the Horthy system, the `Hungary of the gentry´. The adherents of radical change were also in a minority, as the combined support for the Communists and the National Peasants´ Party did not amount to a quarter of the votes cast. (Furthermore, the HCP had eschewed extreme radicalism in its election campaigning.) Most people favoured some blend of democracy with a welfare-oriented economic system, and of Hungarian traditions with a Western orientation - a kind of `bridging´ Hungary, pursuing a middle road. However, it was also clear that the radical left had gathered to itself a sizeable body of support in a relatively short time. Many people, especially among the young, had drawn from the wartime events the conclusion that a catastrophe on that scale could only be resolved by a clean break with everything, or with as much as possible.

As the post-election negotiations to form a new government began, the Soviet Union made a crude intervention. Its obvious intention was to obtain a government that corrected in its favour the balance of forces in the new Parliament. The winning Smallholders´ Party made far from full use of its victory, but it would have liked to reserve the position of interior minister for its general secretary, Béla Kovács, who was highly critical of the Communists. Molotov, after consulting with Stalin and the members of the Politburo, gave Voroshilov three orders: `Insist that the Communists receive the Interior Ministry; Recommend that two posts of deputy prime minister be created additionally and that these be awarded to the Communists and the Social Democrats; Pay attention mainly to ensuring that those entering the new Hungarian government from the Smallholders´ Party and the Social Democrats should be people also acceptable personally to the Soviet government.´

|

Vorosilov, Kliment Jefrimovics |

The Soviet intervention was wholly successful. Formally, only the Smallholders´ Party, with its absolute majority, had a right to form the government. However, the agreement mentioned earlier meant that it had to be content with the prime ministerial post, for Zoltán Tildy, the party chairman. Mátyás Rákosi and Árpád Szakasits, along with the Smallholder István Dobó, who was close to the Communists, became members of the government as state ministers. Most ministerial portfolios were taken by Smallholder politicians, but the HCP obtained the vital Interior Ministry, overseeing the public administration and the police. (The minister was Imre Nagy, hitherto in charge of agriculture.)

On February 1, 1946, the National Assembly passed the act declaring Hungary a republic, on which there was almost complete consensus among the political parties. However, Archbishop Mindszenty proposed postponing a decision, or if that was not possible, calling a referendum on what form of state Hungary should adopt. This never happened. The Smallholders´ Party would have liked a system headed by a strong president, but this was prevented by the other parties, notably the Communists. (Ironically, Rákosi argued in Parliament that it would concentrate too much power into the hands of one man.) The 1945 National Assembly did not adopt a new constitution, but Act I/1946 on the form of state was tantamount to a constitution, since it defined the responsibilities and relations of the president, the legislature and the government. The influence of the president on state affairs and the legislature did not become significant. Parliament elected as president of the republic Zoltán Tildy, from whom Ferenc Nagy took over as prime minister.

|

Zoltán Tildy takes the oath of office as president of the republic in Parliament. In the background, from the left, are Antal Bán and István Ries |

Tildy had been extremely cautious with the Communists and sceptical about the future of Hungarian democracy. Nagy, on the other hand, was an advocate of Western-type democracy. He sincerely believed that the conditions for democracy would come once the peace treaty had been concluded, when the Soviet occupation forces would withdraw.

|

Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy addresses the assembly of the Independent Smallholders´ Party (FKgP) |

The shape of a democratic, independent Hungary seemed to be emerging in 1946-7, if not in every respect. There were some significant economic successes. The efforts made with reconstruction were followed by renewed growth. The supply situation improved, and on August 1, 1946, the issue of a new currency, the forint, managed to curb what had become a world-record rate of inflation.

|

Inflation out of control |

The Communists on the one hand and the Social Democrats and Smallholders on the other had sharply different ideas about stabilization. To the latter, it was essential to have outside help. The former wanted to establish a stable currency exclusively with domestic resources. The Soviet Union, however, was clearly opposed to Hungary raising loans in the West (mainly the United States), which left only the Communist approach as the only feasible course. This called for very tight and painful restrictions on personal spending, coupled with strong concentration of existing stocks and resources in state hands. The record rate of inflation had caused money to be abandoned in favour of barter, as the numbers on pengo banknotes sprouted dozens of zeros. Yet this too was part of a conscious economic policy applied by the Communist, as a stage in a process of wholesale nationalization.

The political democracy that emerged from the 1945 elections did not last long. Even as it was born (during the formation of the government), some cardinal elements of `people´s democracy´ were reinstalled into it, including a Communist-controlled Interior Ministry above the control of the law, and covert deals among political parties. Nonetheless, the declaration of the republic and the acts on the presidency and human and political rights made post-war Hungarian democracy exceptional in the region. Hungarian political culture had important traditions, although they applied only in a restricted way. It was no accident that these would cited again so often during the transition to democracy four decades later, in 1989-90.

Please send comments or suggestions.

This page was created: Tuesday, 2-Dec-2003

Last updated: Tuesday, 2-Dec-2003

Copyright © 2003 The Institute for the History of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution